There has been a paradigm shift in economics to address the world’s ecological challenges. In contrast to throwaway culture, circular economy is proven necessary to preserve resources and reduce waste. This means that we must put a lot of thought into the eco-designing of products and their life cycles. When is a product considered obsolete? What should be done with it when its value becomes depreciated? These are all questions that organisations need to ask themselves as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

Obsolescence, a double-faceted phenomenon

A product is said to be "obsolete" when it loses its useability, although it may still be in good condition. As Kevin Boissie, Valeo's group expert in obsolescence engineering, points out: "Obsolescence is a state, and the consequence of an event that directly impacts the use, utility, operation and/or alters or renders a product unusable."

Obsolescence is generally divided into two types:

- Functional obsolescence refers to a product that no longer suits its intended use from a technical, regulatory and/or economic point of view. This may take the form of incompatibility with new equipment, for example.

- Evolutionary obsolescence refers to a product that no longer responds to consumer desires. Commonly referred to as a 'fad', it occurs when new products come onto the market.

This phenomenon not only has a significant economic impact as it leads consumers to continually purchase similar products when their own become "used" or “irrelevant," but it also has an environmental impact due to the phenomenal amounts of waste this cycle generates.

Does a phone become obsolete in 5 years?

For technology giant Apple, for example, a model is considered obsolete when it has not been on the market for more than seven years. Those that have not been on the market for more than five years (but less than seven years) are labelled as older products.

However, in Europe, shops do not distinguish between old and obsolete models. In other words, the list of products in circulation for five years is considered obsolete. Apple stores no longer provide any hardware repairs or parts for these products, with a few exceptions. A manufacturer, therefore, apparently has the ability to “force” product obsolescence through the decisions they make regarding its repair and maintaining it in a functional state.

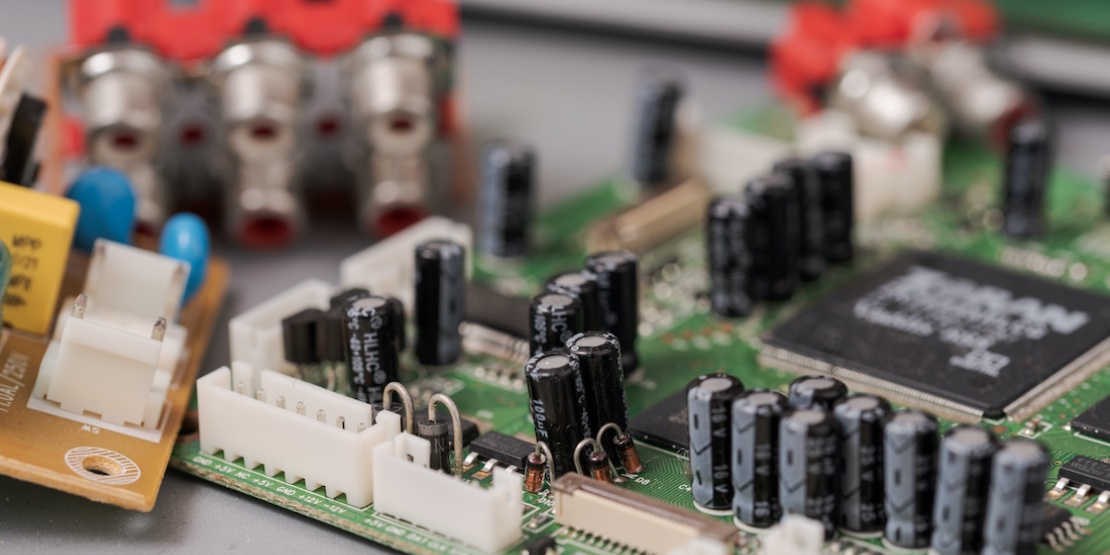

This example reminds us of the need to change our thinking and extend the life of these products, even though they may have lost some of their value. This holds particularly true for electrical and electronic equipment, which greatly impact the environment.

Obsolescence is not an end in itself!

This does not mean that you should throw away your old electronic products! An obsolete or old product can continue to function with new updates or can be given to other players in the market who, in turn, will repair and refurbish it to extend its use. Once you find out that manufacturing a computer emits on average 80 times more CO2 than the energy consumed during one year of use, it seems crucial to maximise its lifespan rather than simply purchasing a new product.

Extending the lifespan of manufactured products is essential if we want to reduce the carbon footprint of our lifestyles. It is actually one of the main levers for significantly reducing our environmental impact. This applies to vehicles, textiles, and furniture as well as to electronic equipment, for example.

Public opinion is also moving in this direction. According to a Eurobarometer survey, 79% of Europeans believe that manufacturers should be obliged to make it easier to repair electronic equipment or replace parts. But that's not all: 77% of the people surveyed would rather have these same appliances repaired than replaced.

Companies can address this in different ways. They have the option of donating, reselling, or recycling products they no longer use, as well as the option of buying refurbished or upcycled products, for example. Today, they turn to recognised players in the market, who offer reliable, turnkey services for each of these options.

Regulation in this area is accelerating

Regulations are increasing to combat product obsolescence.

Repairability index

Spare parts

Since 1st March 2021, European manufacturers have been obligated to make spare parts for certain electrical appliances (refrigerators, washing machines, tumble dryers, dishwashers, etc.) available for a longer period of time and at a reasonable price.

At the same time, the Members of the European Parliament have also defined the right to reparation as a priority and intend to expand on the legislative framework to promote the cost-effectiveness and universality of repairs.

Consumers, distributors and manufacturers all have a role to play in the circular economy, by delaying product obsolescence as long as possible. These actors can learn how to recognise sustainable practices and technology; or make sure future products and services match up to what is considered a durable design. It is also an important area for procurement departments to consider when calculating the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) of the goods and services purchased, with a view to sustainable consumption and optimising expenditure.

- Download our "Procurement policy and CSR" white paper